It’s been two years since the early pandemic crashed the market. Despite a strong recovery, many investors may feel emotionally worn out. Now we are faced with the geopolitical stress of the Russia-Ukraine war and the accompanying market volatility—layered on top of uncertainties already in place, such as inflation and job growth. An investor with frayed nerves could be forgiven for wanting to “do something.”

Historically, that desire—though completely understandable—tends to work against long-term portfolio success. Yes, there may be small tweaks during periods of market volatility as relative-value and tax-loss harvesting opportunities come into view. But typically those changes occur the margin, where they are unlikely to fully satisfying that pesky drive to act.

There’s a terrific quote from legendary basketball coach John Wooden that can help counter action bias. It’s one all investors should take to heart: “Do not mistake activity for achievement.”

It turns out humans are hardwired with what behavior economists call “action bias.” Countering that tendency is difficult—whether you’re an athlete or an investor.

Lessons from soccer goalies

In the mid-2000s, an Israeli psychologist performed a study on soccer penalty kicks, in which a player takes a shot on goal with no defenders on the field other than the opposing team’s goalie.

Given the talent of the kicker and the size of the goal, penalty kicks have a high success rate. However, the research team found that success rate was higher than necessary, when seen from the goalie’s perspective.

Their statistical analysis showed that if the goalie were to stay put in the middle of the goal—rather than “selling out” by diving either left or right—the fewer penalty shots got in.

The research team assumed this new information would be groundbreaking, leading to changes in how soccer was played. To their surprise, however, they discovered most soccer teams already had those same statistics. Goalies knew their actions were decreasing their chance of success.

So why were they diving? The reason given was universal. They said, “I can’t just sit there and do nothing.”

Lessons for investors

Now, if John Wooden had been a soccer coach, I suspect the goalies that played on his teams would have stayed in the middle of the goal during penalty kicks. He would have helped them overcome action bias.

Though Wooden was coaching at UCLA—where his teams won 10 national championships—prior to the coining of the term “action bias,” he didn’t need the term to recognize and deal with its destructive potential. Wooden understood that human beings are hard-wired to believe we provide more value when we are doing something than when we are doing nothing…even when “nothing” is clearly the smart move.

In soccer, a blown penalty kick save can make for a bad game—but it’s still “just a game,” as my grandmother used to tell me. In investing, though, the stakes are higher. Action bias is powerful. It can ruin lifelong wishes, hopes, dreams and desires.

During market tumult, we can’t help but to see others like us taking action—selling and then buying and then selling again. As they do, they are “doing something”…chasing economic, scientific and medical information with a fervent and maniacal goal of beating the market. This desire can be strong during any economic crisis. But paired with a social environment in which we are literally being asked to “do nothing” to save lives, action bias has even more destructive potential, in our view.

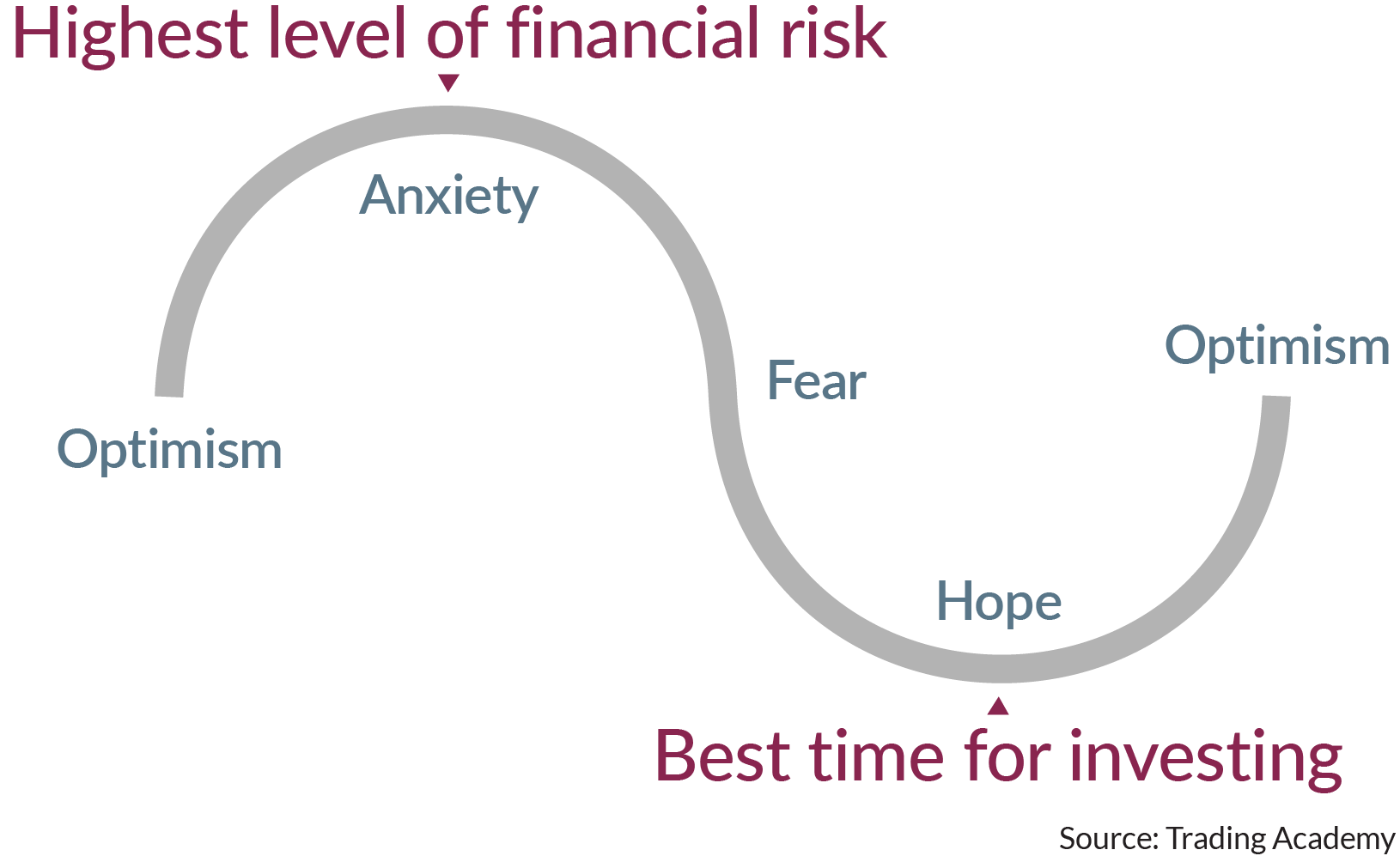

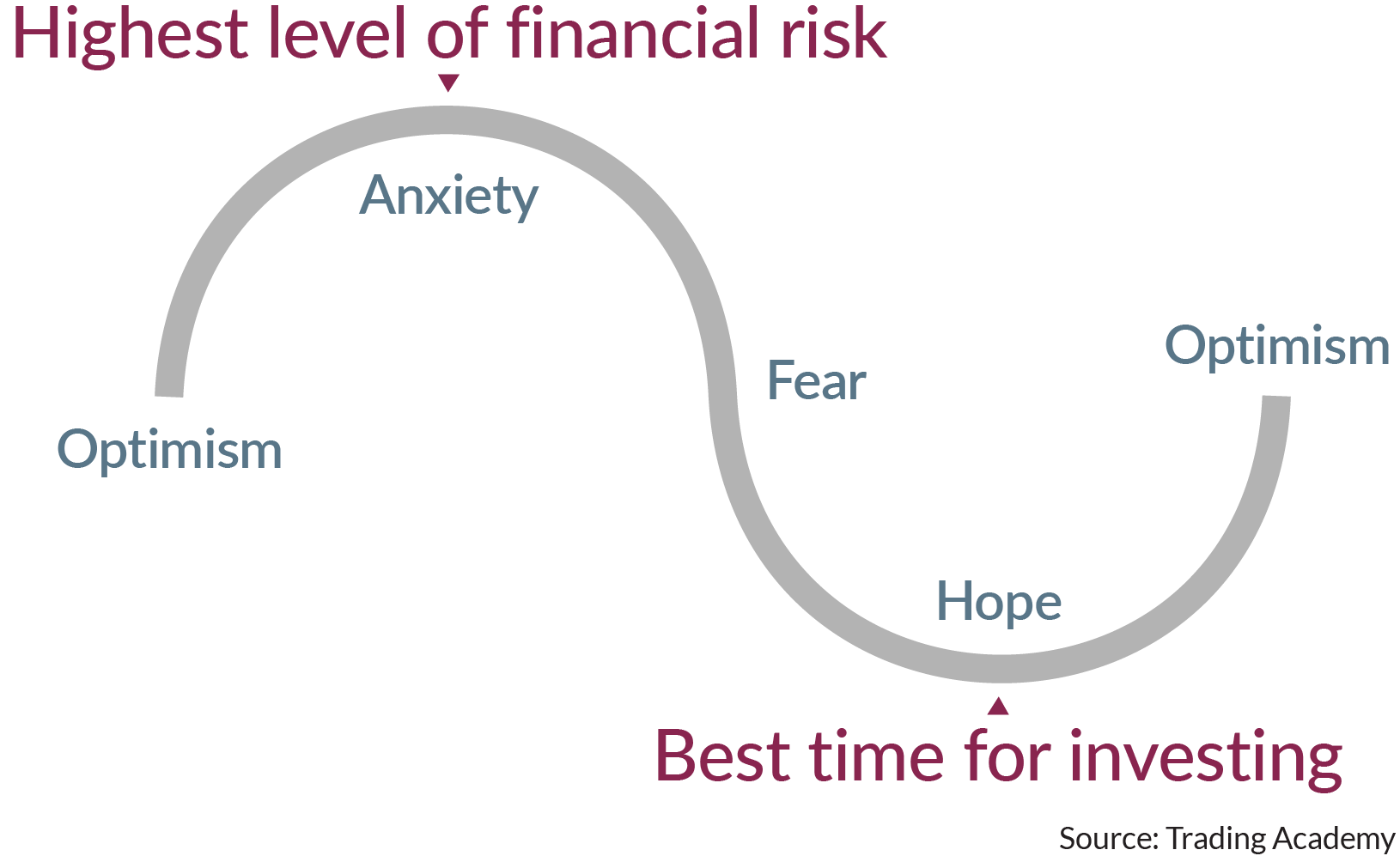

Exhibit 1 shows the different types of emotions you may experience when the market is high and low.

Perhaps it’s a little easier now to understand those soccer goalies! Action bias can eat at our brains, hearts and souls. So, if you don’t have John Wooden at your side, reminding you not to mistake activity for achievement, you need to coach yourself. Be wary of following the crowd. Remember that selling when others are selling and buying when others are buying ultimately amounts to “selling low and buying high.” Doing so is the epitome of engaging in activity without achievement as there is no chance of success.

Instead, embrace what the Chinese call wu wei, the art of non-doing. Remember that your financial plan was built with a purpose of meeting your individual goals. Remember it was built with the knowledge that periods of severe uncertainty and volatility would inevitably come.

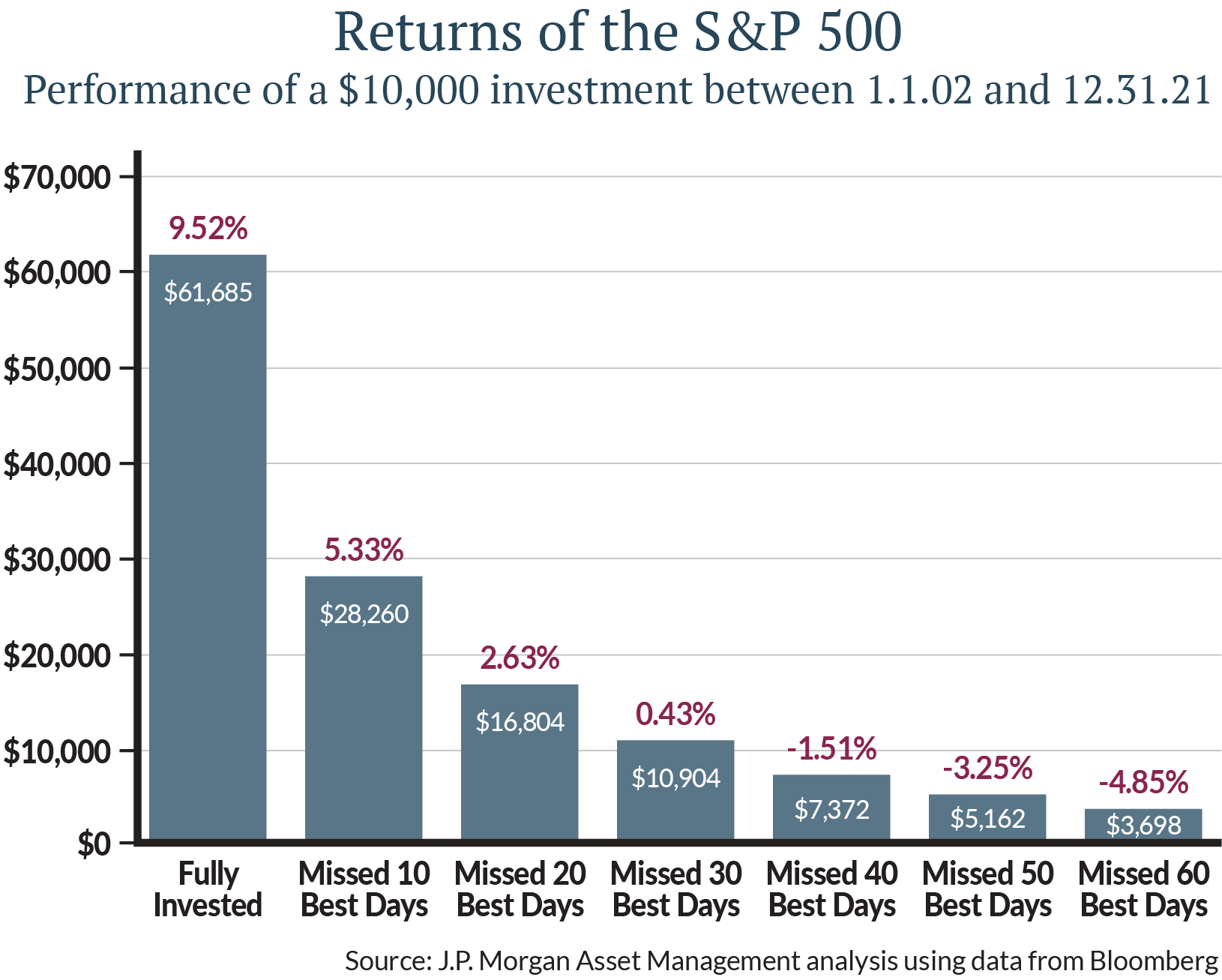

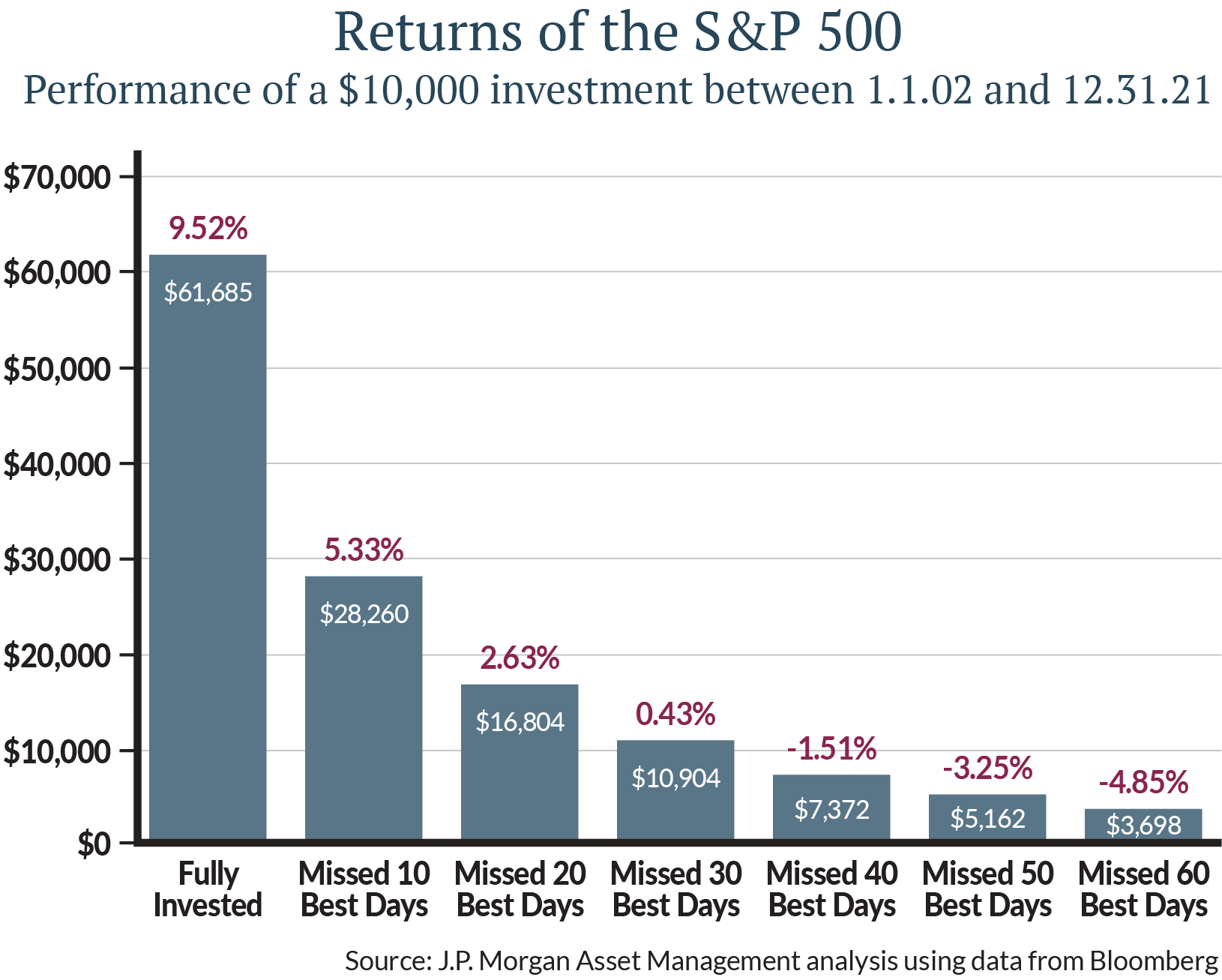

Returns of the S&P 500

Performance of a $10,000 investment between January 3, 2000 and December 31, 2019. Exhibit 2 shows the returns of the S&P in 2021 and six of the best 10 days occurred within two weeks of the 10 worst days.

Plans are designed to withstand difficult times. By all means, revisit your plan and adjust it if needed—with an eye toward your long-term happiness, looking beyond these uncertain, scary times. But as you do, be willing to know it’s possible—perhaps even likely—that the best thing you can do right now is to “just sit there and do nothing.” John Wooden would be proud of your wu wei.