SUMMARY

In the first article of a six-part series, Joe Maier, Director of Wealth Strategy, explores the “why” of your charitable mission statement. With a financial plan as your starting point, you can divide each dollar of your net worth into three categories – independence, legacy and philanthropy. Within the philanthropy focus, you will craft your charitable mission to make maximum impact. Learn how to define the “why” of your giving strategy through the lens of hypothetical family, the Howards.

One of the most frequent questions we are asked as advisers is “What is the right vehicle for my charitable giving?”

Given the significant interest in philanthropy, it’s no surprise that the internet has plenty of questionable material on the subject—advising and educating (and often advocating) about direct giving vs. donor-advised funds vs. private foundations. These articles focus on the how, including costs, control, tax benefits, ongoing burden and legacy.

But very few start at the right place, why.

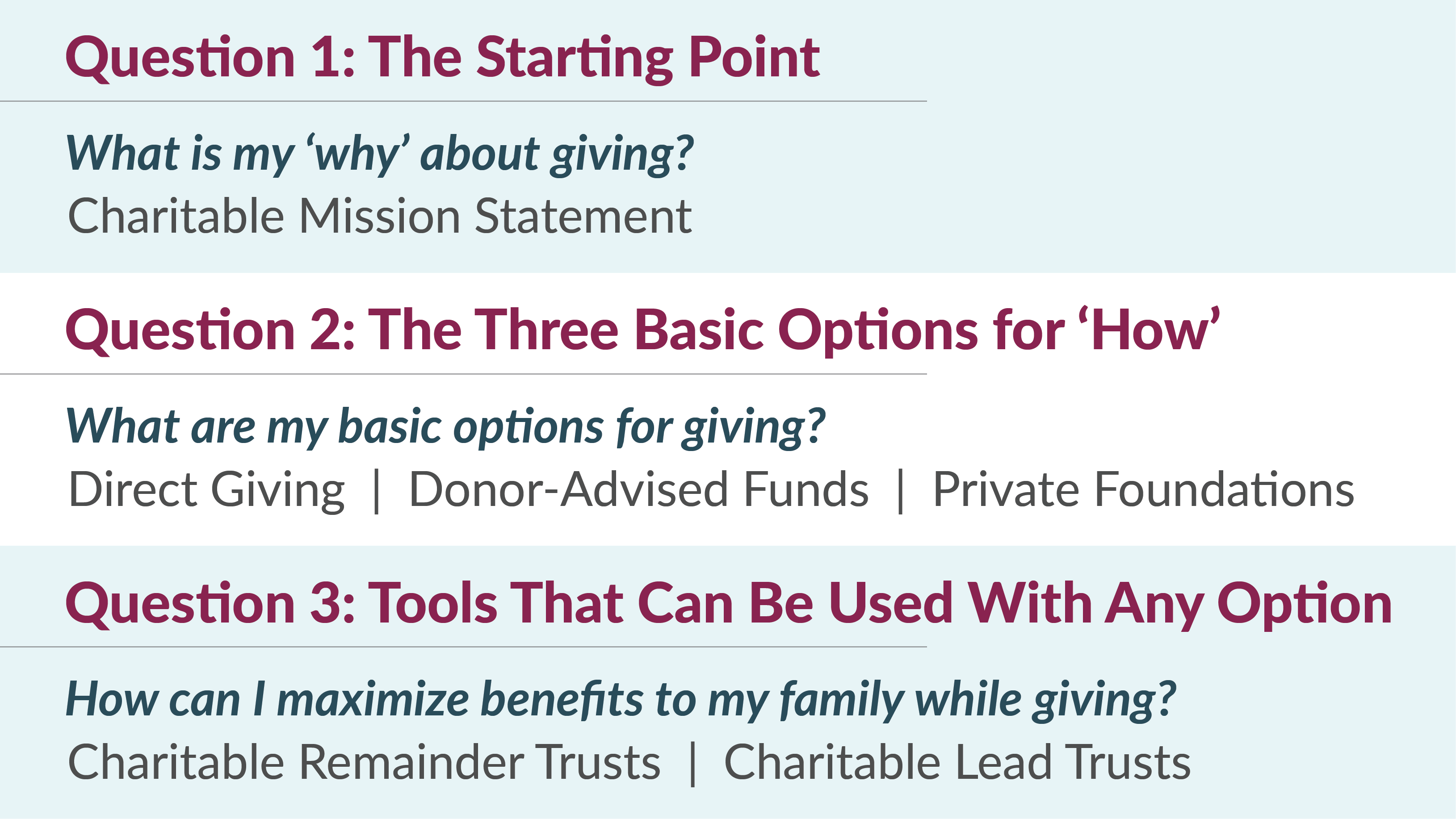

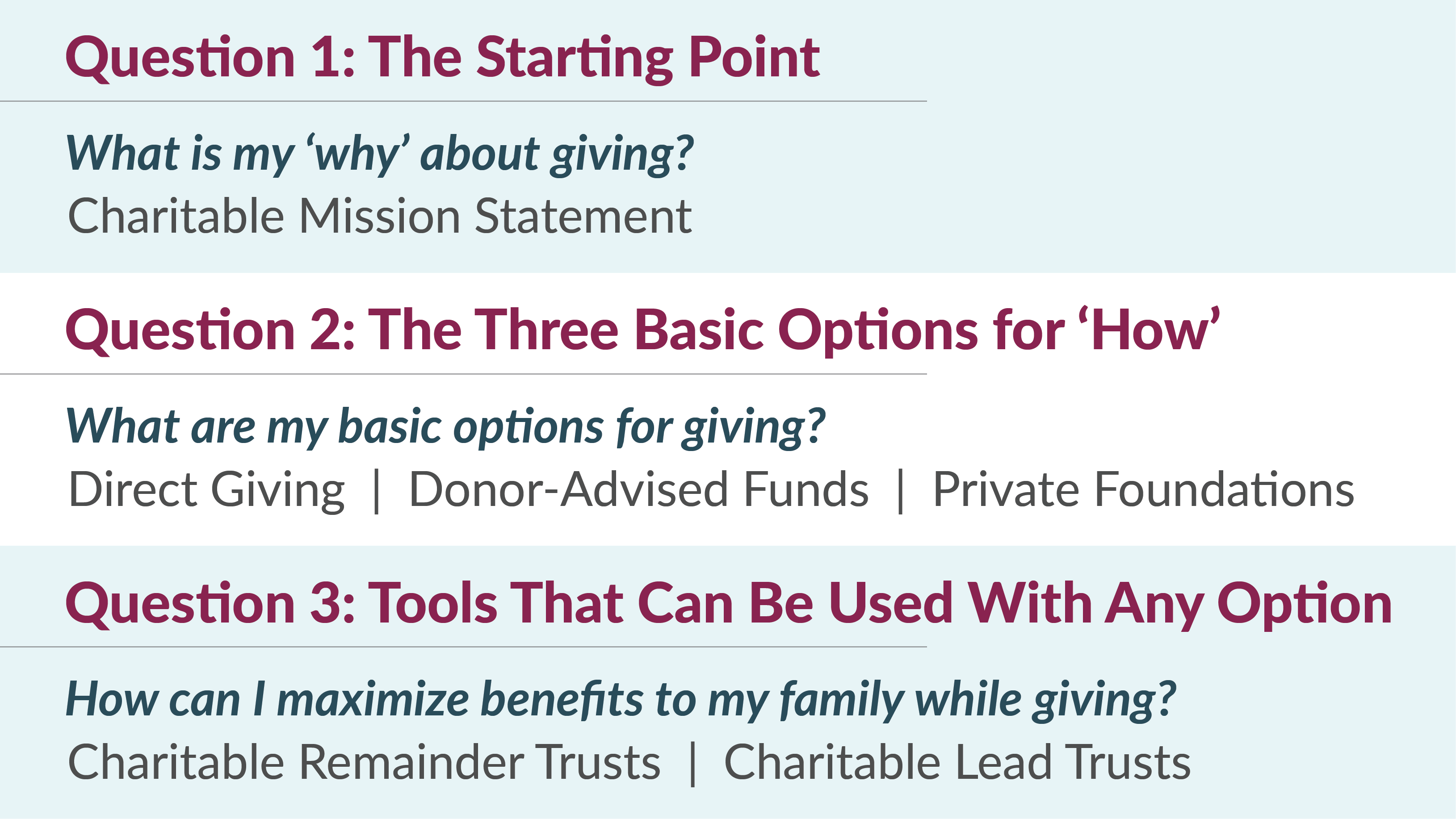

That’s the subject of this article, the first in a six-part series exploring how to create and implement a charitable effort. Let’s take a moment to get the lay of the land for the series as a whole, which is structured as answers to three basic questions. For example, in this first article we will look at how charitable mission statements answer the question of “What is my ‘why’ about giving?”

For the first four articles in the series, we will examine the issues through the lens of a hypothetical family, the Howards. For the final two installments, we’ll introduce a second hypothetical family as we explore charitable remainder trusts and charitable lead trusts. Those two articles will be the most technical in the series.

With that, let’s start with why.

The Financial Plan as Starting Point in “Getting to Why”

Since a financial plan is a strategy to use your assets and income to maximize your happiness, it is the foundation on which a charitable mission starts.

For some people, the sole focus of a financial plan is their own financial independence. Their financial strategy is to use every dollar they have to pay for their own needs and wants. Others expand the focus of their planning to family members. Their happiness is found by using their wealth to enrich the lives of those they care about. And finally, there are others for whom a large part of their happiness can be shaped by making an impact beyond themselves and their family.

For that final group, a focal point in the financial plan is dividing each dollar of net worth among independence, legacy and philanthropy. How you divide each dollar is based on what you want your wealth to accomplish. The charitable mission, then, expresses your objectives within the philanthropy category.

Crafting a Charitable Mission

Your philanthropic focus might be on aiding a particular organization, furthering a favorite cause, assisting several causes or building a multi-generational philanthropic family culture. What’s crucial is to determine and express why your chosen focus aligns with who you are. This why—more than any technical details or even dollar figures—becomes the starting point of your charitable mission statement.

Why you have elected to use a portion of your assets and income for charity rather than yourself and your family will be highly individual:

- It can be very you centric (This is why giving makes me happy)

- It can be very organization centric (This is why I want to support the University of Wisconsin)

- It can be very cause centric (I want to help eradicate childhood cancer)

- It can be very family centric (I want to create a multi-generational culture of giving in my family)

Or, a charitable mission statement can be (and generally is) a combination of those. Creating one forces you to really think about connecting to your why—and making certain that the giving strategy, as part of your broader financial plan, will further your happiness.

Charitable Mission Statements in Practice

Once established, a charitable mission statement helps you connect your happiness to a philanthropic purpose. It provides clarity based on your convictions about the organizations and causes that matter enough to you that you are willing to divert funds from yourself and your family. It also helps you stay clear about the causes you do not intend to support, so your assets can make maximum impact in your focus areas—and therefore maximum impact on your happiness.

Meet the Howards

Dean and Jessica Howard own a thriving industrial supply business. Despite worries about Amazon.com and other online forces reshaping their industry, Howard Supply Co. continues to own a significant share of the wholeseale market in its region.

Both Dean and Jessica work in the business. Dean, who grew up in the industry, heads the company’s sales force. If he’s not at one of the firm’s several warehouses, he’s on a jobsite with a customer. Jessica, formerly a junior partner at a global accounting firm, left that position to manage the firm’s finances and all aspects of its supply chain. Dean and Jessica are the only owners of the company.

Dean and Jessica have long been generous donors to charitable causes, but their focus has both intensified and narrowed in the last two years. Their son, James, suffered and recovered from a rare type of childhood cancer. He has been symptom free for the past sixteen months. At the end of last year, Dean and Jessica wrote a large check to the nonprofit hospital system where James received outstanding care. That expression of gratitude was many times the size of their prior annual charitable contributions, combined.

Before year-end of this year, Dean and Jessica would like to once again make a major gift. They consider themselves a permanent part of a small community of families, spread around the country, with children facing the illness James recovered from. Over recent months, Dean and Jessica have become aware of other nonprofits dedicated to the care of children suffering from this illness and to the development of additional treatments. Dean and Jessica are prepared to write one or more substantive checks totaling as much as they gave last year, but they have questions about where to direct the funds and whether to attach their gift to specific initiatives or simply to designate it for general use.

Dean and Jessica have a very clearly defined “why”. With this clarity in place, it’s now time to turn to “how.” In Part II of this series, we’ll look at the first of the three basic options—direct giving—using the Howards to illustrate.